Talking Uniforms, Logos, and Aesthetics With Music Engineer Steve Albini

From indie-rock to the World Series of Poker — and a lot in between — the renowned musician and audio engineer has had a surprisingly uni-adjacent career.

If you’ve been a fan of rock music over the past 40 years, there’s a decent chance you’re at least vaguely familiar with Steve Albini (shown above). He’s recorded, engineered, and produced literally thousands of albums during his career — some by super-obscure bands that almost nobody’s heard of and others by big names, including Nirvana’s In Utero; the Pixies’ Surfer Rosa; the Breeders’ Pod; PJ Harvey’s Rid of Me; Jimmy Page and Robert Plant’s Walking into Clarksdale; and countless others. Many of those albums were recorded at Albini’s own studio in Chicago, Electrical Audio, which he opened in 1997. He’s also played in several bands of his own, most notably Big Black (1982-1987) and Shellac of North America (1994-present), authored a slew of influential and sometimes controversial articles about the music industry, and, more recently, had a side career as a professional poker player.

While Albini and I have never hung out or shared a meal or anything like that, we are not completely unknown to each other. I’ve been a fan of his music and writing since first encountering them in 1985; he was a fan of my 1990s fanzine, Beer Frame: The Journal of Inconspicuous Consumption, which led to him writing the foreword to my 1997 book, Inconspicuous Consumption: An Obsessive Look at the Stuff We Take for Granted. But that was ages ago, and I’ve never gotten the impression that he cares about sports in general or sports uniforms in particular. So I was surprised when this tweet showed up in my Twitter mentions a few months back:

Why would someone who doesn’t care about sports be following me on Twitter? And why would he be tweeting about following me on Twitter?

The more I thought about it, though, the more I realized that while Albini may not be a sports guy, he’s always shown an interest in design and aesthetics, and his career arc has included a surprising number of uni-adjacent junctures. I figured it would be fun to pick his brain about all of that. So after I saw his tweet, I sent him a note (our first interaction, I’m pretty sure, since that 1997 book was published) and asked if we could do a Uni Watch interview. He said sure.

It took a little while for our schedules to align, but it was worth the wait. Here’s a transcript culled from two separate Zoom conversations we recently had, edited for length and clarity.

Uni Watch: The impetus for this conversation came a few months ago, when you mentioned on Twitter that you follow my account. I was surprised by that, because I never got the impression that you cared much about sports or sports design. Are you into all of that?

Steve Albini: Not at all. But every day my feed is saturated with all of these design details that you cover, and just knowing that there’s somebody out there clocking all of it makes me feel good. I have an appreciation for people who have arcane obsessions, and over the the long arc of your career, arcane obsession is probably the one constant. So I marvel that you have somehow created a life by just making observations about the way things look. I’m charmed by that, and I’m particularly charmed by how minute and microscopic the detail is in some of your observations, and that there’s enough public interest in that to sustain you.

UW: Well, thank you — I really appreciate that. I like to say that not everybody is into what I do, but the people who are into it tend to be, you know, really fucking into it.

Albini: I especially like that there’s kind of an obsession in your circles with removing the logos of sports merchandise companies, and you even offer Uni Watch-branded seam rippers specifically for removing the New Era logo from ballcaps, which I think is an incredible merchandise option. I mean, I can’t honestly can’t think of a merchandise item more specifically arcane than that. The office manager here at our studio had a White Sox cap, and I said, “Would you like me to clean that up for you?” He didn’t know what I was talking about, so I took it away and spent 15 minutes getting rid of the New Era logo. And he immediately appreciated it. It would never have occurred to him to do anything about it, but it obviously looks better without that big promotional logo on it.

UW: I’m glad he appreciated it, because there are some fans who would say — and who do say — “Oh, now it’s not as official, now it’s not as authentic, now it’s not like the ones the players were on the field.”

Albini: That’s an argument toward authenticity as opposed to an argument toward aesthetics. And I think just the aesthetics of the cap are better without the dumb logo on it.

UW: I’m in total agreement with you there, obviously. What about when you were a kid? Did you play youth sports of any kind? And if so, did you get geeked out about your own uniform?

Albini: Yeah, I played Little League, I played Pony League, I played American Legion ball. I was always scrawny, so I played baseball up until my late teens, when everybody muscled up except me. I wanted to be a catcher, so I was constantly getting steamrollered. I would stay there in position, blocking the plate waiting for the throw, and I would just get creamed every game.

UW: Did you care about wearing your uniform just so, or your catcher’s gear?

Albini: No. For a long time I used a hand-me-down 1950s catcher’s mitt that was my uncle’s. It was like this big, dumb sofa cushion of a catcher’s mitt. I eventually got my own mitt. But I’m not that into all the specifics — again, what I appreciate about Uni Watch is your enthusiasm, the obsession over all the logos and details.

UW: What about your studio, Electrical Audio — do you have a company softball team or anything like that?

Albini: Chicago has an adult baseball league — the Chicago Metropolitan Baseball Association — that’s been around since the 1920s. So in 2003 we put a team together, called the Winnemac Electrons, “Winnemac” referring to Winnemac Park, where we played our home games. The team started as as Electrical employees and Electrical-adjacent kind of people. We were all in our 40s, with a lot of heavy smokers. It was sort of a drinking society of baseball enthusiasts, well past their prime, who were looking for a way to play baseball again. So that’s how the Electrons were born. The team still exists today, although I think only one of the original Electrons is still on the roster.

UW: Did you play?

Albini: I was only on the team for a couple of years. I didn’t play much because I’m bad. I’d basically be subbed in to play first base or something as a mercy, you know, out of pity. I don’t have any photos of me playing. I was kind of a mascot more than a player.

UW: And the opposing teams would just be other adult teams in your league?

Albini: Yeah. The most interesting one was the team that had all of Ozzie Guillén’s kids when he was managing the White Sox. So we would pull up to Winnemac Park in our various jalopies and there would be a row of a half a dozen black Escalades lined up next to the fence.

UW: What are the Electrons’ team colors, and how were they chosen?

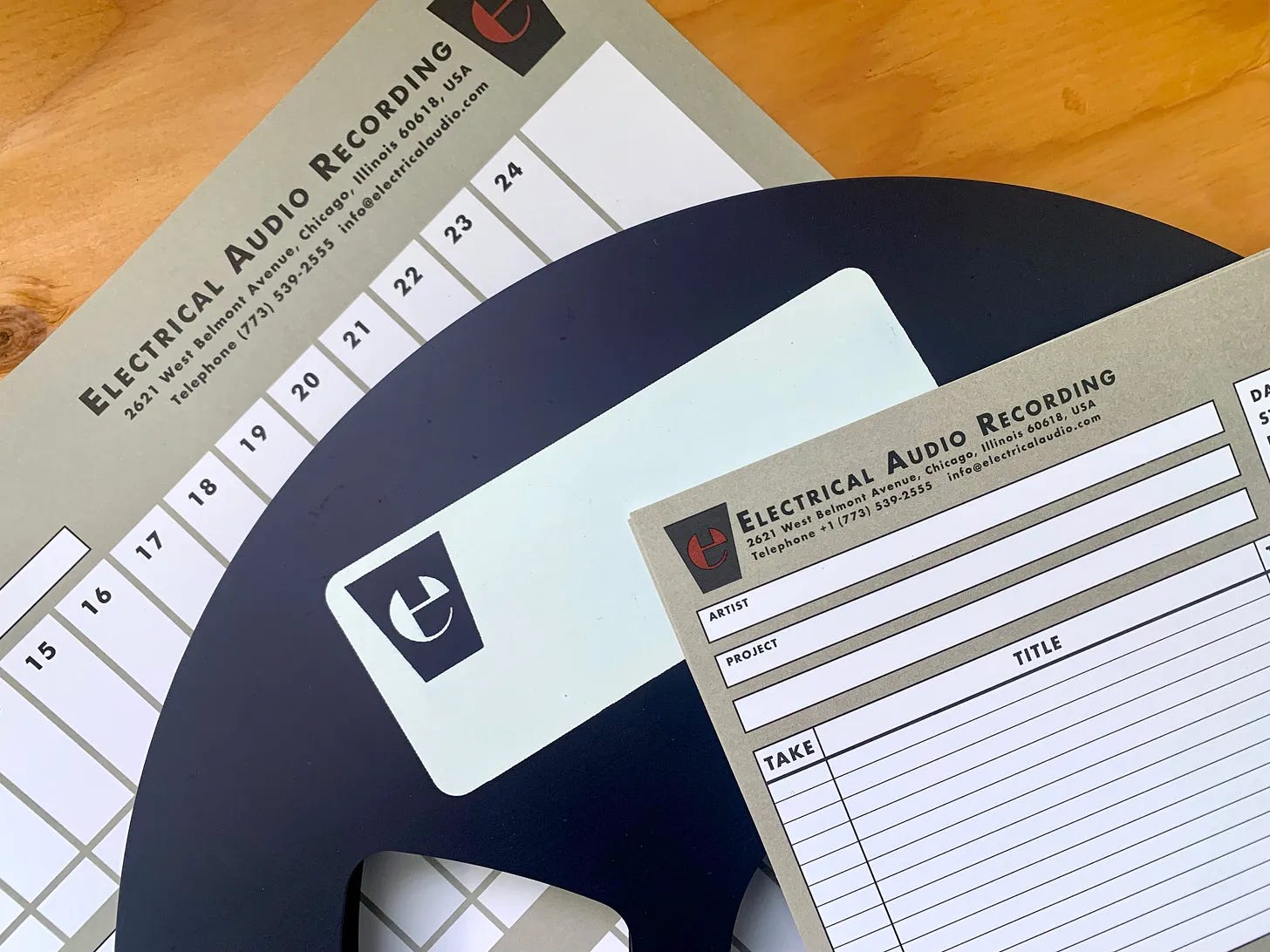

Albini: Maroon and grey, which are two colors that are all over the Electrical Audio building and on our letterhead, our track sheets, our box labels. At one point we had sort of old-school uniforms with embroidered lettering and woolens and stirrups and yada-yada, and then later we opted for more budget-conscious uniform choices.

UW: Did you have a hand in the uniform design?

Albini: I mean, we just picked a typeface that was available from the uniform place. We didn’t give them graphics or anything. The caps did have the Electrical logo on them.

UW: What number did you wear?

Albini: 41, I think because that’s how old I was for our first season. When I stopped playing, they actually retired my number [as shown on the team’s “History” page].

UW: Was there a ceremony for your number retirement, and do you have a framed No. 41 jersey hanging on a wall?

Albini [laughing]: No, no, nothing like that. The most formal thing that ever happened with the Electrons was, after we’d win a game, we’d go to a bar that was our regular hangout and I would pop for a round of wings.

UW: I know you got a journalism degree in college, but you obviously know a lot about design, and you were a photo retoucher at one point. So did you also study visual arts and graphic arts?

Albini: Not really. When I was in high school, I had more of an interest in graphic design, sort of as a practical matter. I was in a punk band and we were doing flyers and record sleeves and and posters and stuff like that. And when I worked at the school newspaper in college, I had access to a process camera, so I could be of use to the punk community for things like making PMTs — that’s a photomechanical transfer, which is a large-format reproduction of graphic art that would then be used as reflective art to make negatives for printing.

I also worked at a T-shirt screen-printing shop — not because I had an interest in screen-printing, but so I could bootleg band shirts for my own band and my friends’ bands during off-hours. I had it down to a science: I knew when the boss’s car would pull away, I knew there were certain T-shirts that were inventoried and certain shirts that weren’t, so I could get the blank shirts that weren’t being inventoried and print up a dozen for my friends who were playing a show. There’s a French term I can’t remember, but it basically means you subvert capitalism by clandestine means and make use of the tools of capitalism for your own ends. I did a lot of that.

UW: So it sounds like for this graphic arts stuff, you were mostly self-taught.

Albini: Yeah. I did take some graphic design books out of the library and learn about things that way.

UW: One detail I love about your studio, Electrical Audio — and I think you’ve done this right from the start when you opened in the late ’90s — is that you and the other employees wear jumpsuits with the studio’s logo on the back.

Albini [standing up to demonstrate]: I’m wearing an Electrical jumpsuit as as we speak. But that’s not a uniform…

UW: Oh come on, of course it’s a uniform!

Albini: We’re just providing work clothes for everybody.

UW: At the very least, it’s “standardized attire” — can we say that? Anyway, whatever you want to call it, why did you choose to go with the jumpsuits?

Albini: It’s actually a good story. While we were in the construction phase of the studio, we had an ad hoc construction crew that was mostly people from the music scene — people I knew from one place or another, most of whom were not tradesmen, who didn’t know what they were doing but were learning how to do it by building the studio.

During the studio construction, obviously, there’s a lot of manual labor. Your clothes get fucked up and things get dirty. This one guy, Bill Skibbe, he had a side job working as a motorcycle mechanic. So he started wearing his jumpsuit when he was working on building the studio — the same jumpsuit he wore as a mechanic. And other people started wearing jumpsuits as well, from his influence.

During that period, I had to go to England for an extended period to do an album that was the longest I’ve ever worked on a single record. I was gone for about six months. And during that period, the construction continued apace at the studio. When I came back from England, everyone in the crew was wearing jumpsuits. So when I walked in for the first time after that six-month absence, somebody handed me a folded-up jumpsuit and said, “Here you go.” I immediately put it on, and that was it.

UW: So this wasn’t something that came from the top down — it bubbled up from below.

Albini: Yeah. And it’s a supremely practical thing, because when you’re working in the studio, you’re basically doing light manual labor all the time. Like, you’re crawling around under the drum kit plugging stuff in, or you have to move all the amplifiers from one room to the other, or whatever. It’s not desk work. So it’s nice to have extra pockets where you can stick the mic holder or the microphone itself or whatever you need. And that way you don’t fuck up your regular clothes.

UW: At what point did you decide to put the Electrical logo on the back of the jumpsuits?

Albini: When we realized we were going to be getting a bunch of jumpsuits, we figured we might as well put the logo on the back of them.

UW: Who created the logo?

Albini: I doodled it out, like most things.

UW: Is there any significance to the jumpsuit colors? Like, do engineers wear one color, the techs wear another color, and so on?

Albini: No. They’re all drab — forest green, navy, charcoal, whatever.

UW: What brand are they?

Albini: Red Kap. We used to get Roebucks, which were the Sears Roebuck work clothes line. And we’ve experimented with other ones — we’ve had some samples from various other people — but the Red Kap ones are the ones that we’ve sort of standardized. They usually last five or six years until they wear out, and then we have to buy a new batch.

But a while back we had an intern who was a real character, named Andrew Mason, who went on to become the founder and CEO of Groupon. He’s an optimizer — like, he moves into a situation and tries to optimize things right away. He wasn’t fond of the jumpsuits because they’re this synthetic material, they’re polyester. It’s not a nice fabric. And he said, “Why don’t I find us some natural-fiber ones? That will be more comfortable.”

So he found some jumpsuits that were all-cotton. We ordered a batch of them and they were fucking ridiculous. They were these giant, balloony things. Bright red, too. They were bright, red, puffy clown suits — if they just had big buttons on them, you could get work as a clown. We even took them to a tailor and said, “Can you make these a little bit less clowny and giant and buffoonish?” So that at least made them wearable. But they also weren’t as durable. They wore out in a couple of years. The red era was kind of a stain on the history of the jumpsuit at Electrical Audio.

UW: Do you ever embroider the person’s name on the chest of the jumpsuit or anything like that?

Albini: No, we haven’t haven’t customized them. The closest thing is Greg Norman, who’s our Chief Engineer — as a gag, we had the Electrical logo printed upside-down and backwards on his jumpsuit, because that way it sort of looks like the letter G, for Greg.

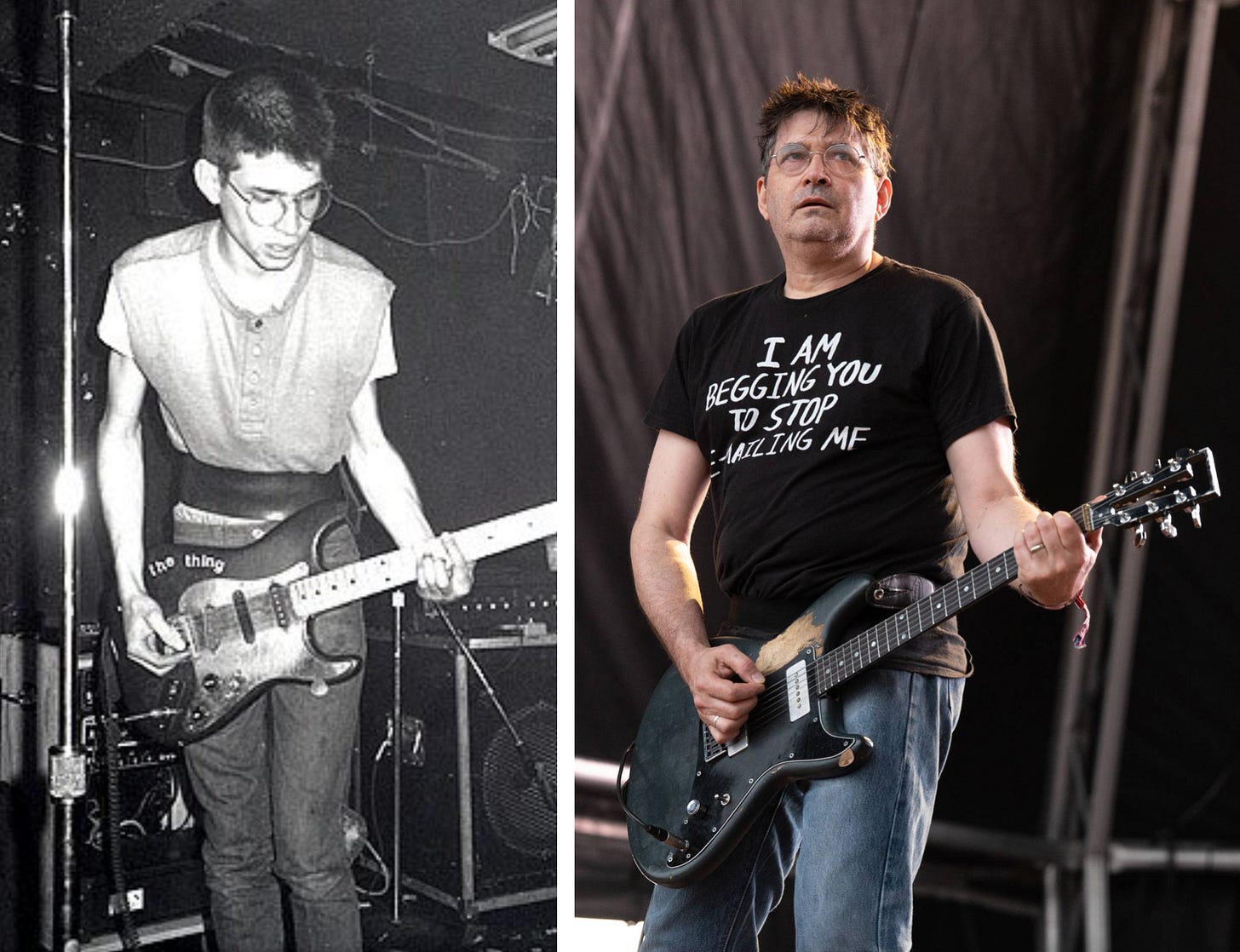

UW: Part of what I cover in the sports world is that there’ll often be one player who really stands out aesthetically for whatever reason, like the football player who has a particularly bizarre facemask, or the basketball player who shoots free throws underhanded, or the ambidextrous baseball pitcher with the weird six-fingered glove. And I feel like you’re sort of that guy in the music world, because you wear your guitar strapped around your waist instead of over your shoulder. When and why did you start doing that?

Albini: I started my tenure as a musician by playing bass guitar in a punk band in Missoula, Montana. The gear available at the local family-run music store in town was a few terrible secondhand guitars and the new instruments they carried were the Peavey brand. So my first purchase, when I was 16 or 17, was a Peavey T-40 bass guitar.

Peavey made very workmanlike instruments — very proletarian, simple, heavy-duty, reliable. And anyone who’s ever picked up one of these things will recognize how insanely heavy they were. The guy who ran the company, Hartley Peavey, had this notion of sturdiness that he wanted his instruments to convey. And he instructed the people who were designing those instruments to make them heavy, so that when you picked it up, it felt substantial. The weight plays no part in the sound or the suitability of the instrument — it just makes it heavy. That’s the impression it’s supposed to make when you pick it up out of the stand — like, “Oh, this is heavy. This must be a serious instrument.”

Anyway, so I was wearing my Peavey T-40 bass guitar conventionally around my neck like everybody else does. But it was heavy and uncomfortable, and I hated it. So I started playing around with the strap and seeing if there was another way to wear it. I quickly came up with this idea of wrapping the guitar strap around my waist, and it immediately took the weight off of my shoulders. It also felt more natural because I have preposterously long limbs — truly ape-like limbs — so having the neck sticking straight out at a distance actually was more physically comfortable for me than having my arm bunched up against my body like I’d have to do if I wore the instrument conventionally. So everything about wearing it around my waist was instantly more comfortable and more natural, and I never looked back. I’ve always done it that way.

UW: Was it also fun to create an onstage look that was different from everyone else’s? Did that appeal to you?

Albini: It didn’t particularly matter to me that it was distinctive or unique.

UW: Really? I’m a little surprised to hear that.

Albini: It sounds dumb when I say this, because I do notice odd stylistic things, but I genuinely don’t care about style, at least for myself. I appreciate when other people have a good visual sense. But in my personal life, I don’t wear stylish clothes; I wear functional clothes. I don’t care about the style of my car. That sort of stuff doesn’t matter to me. I mean, look at me — I don’t try to project an image. I’m just a guy.

I care much more about the design of artifacts — things like record sleeves, flyers, stationery, books and magazines, stuff like that. The design of artifacts matters way more to me than me having a personal style.

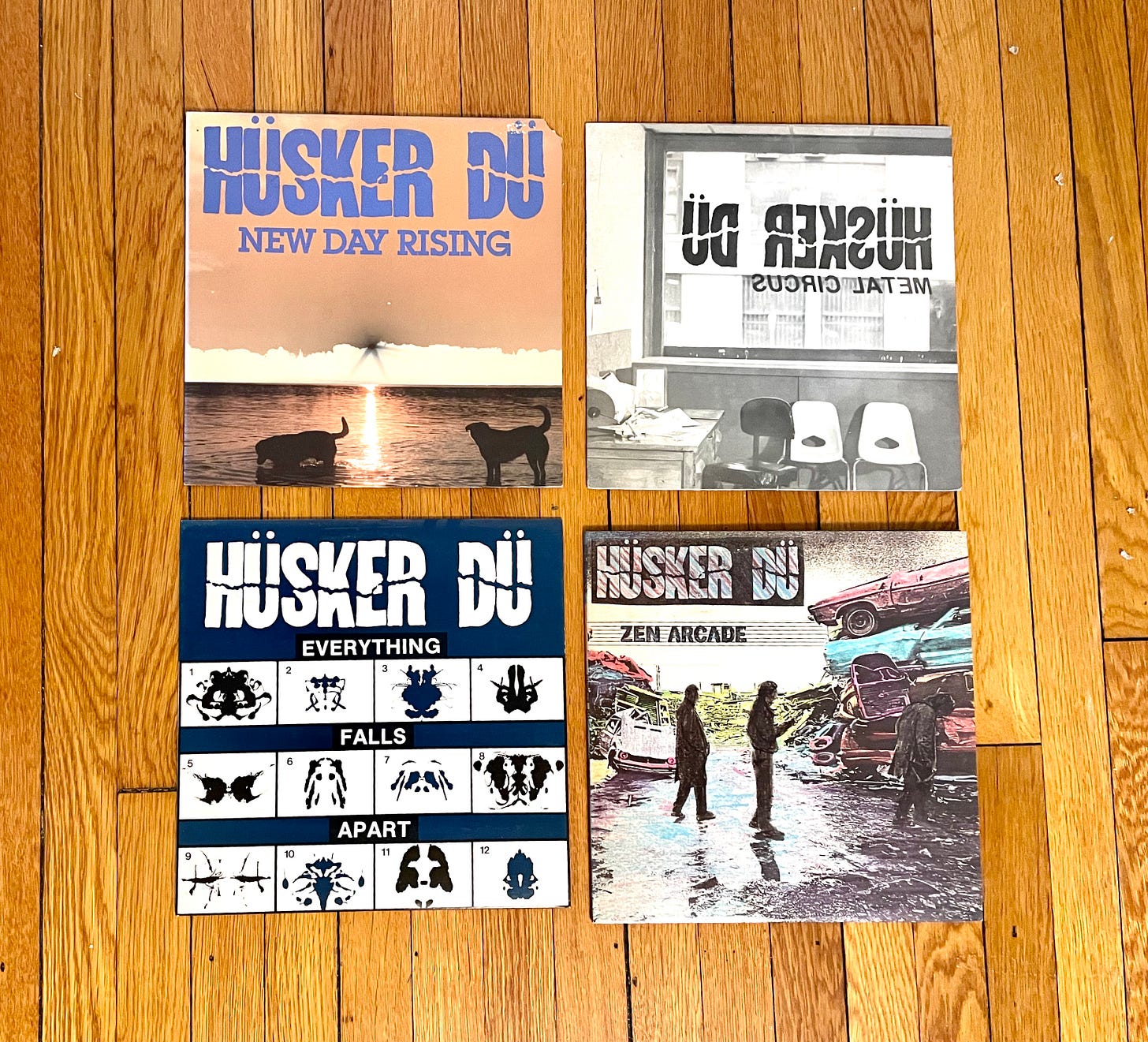

UW: That leads us to the next thing I wanted to ask you about about, which is logos for rock bands. Bear with me here while I set this up: Going back to the ’60s, there were some bands that would have recurring logos that you’d see on flyers or maybe on the bass drum, like the Who and the Beatles. And then in the ’70s you started seeing bands that used logos in a way that feel more like corporate branding, like Chicago or the Rolling Stones or Led Zeppelin. And by the early ’80s, which is when I started caring about music seriously, I realized that heavy metal and hardcore bands tended to have logos that they would use repeatedly on all their album covers. And I didn’t really have the language for this at that time in my life, but this was essentially branding. I remember thinking, “Oh, every Hüsker Dü record or every Black Flag record, they always use the same logo,” and it almost felt like each album was the next issue of a magazine or something like that. And I felt very conflicted about that, because I mostly hated heavy metal but I mostly loved hardcore. And I was trying to sort of sift out in my mind whether I thought a band using a consistent logo was a good thing or a bad thing.

And so I say all that to set up this question: How do you, as someone who obviously cares a lot about music and about design, how do you feel about striking that balance between the band and the brand?

Albini: I’m not going to indulge your “brand” concept just because it creeps me out. But having lived through that era you’re describing, and having been responsible for making record covers and flyers and ads during that era, I will tell you that a very large component of it is that if someone has already made a logo, and that logo exists somewhere, they are going to reuse it simply because there would be an additional expense making something new. As a practical matter, at least from the punk and hardcore side of things, paying for things was the last resort, right?

UW: But you don’t really need a logo at all. You can just incorporate the band name into the album cover art, or even not put the band name on the album cover at all — there are plenty of cover designs that are just a photograph or an illustration.

Albini: Yes, those are all perfectly viable options.

UW: How have you approached this with some of your bands? Did you think about having a logo, and whether that was a good thing or a bad thing?

Albini: There isn’t a consistent logo or image that was used for any of them. I made no attempt to stylize things in a way that made them immediately identifiable. In the ’80s, Big Black had a visual style of its record sleeves and artwork and stuff, but 100% of that was due to the practical aspects of getting record jackets printed cheaply. For the first Big Black record, I did a simple paste-up of some photographs and type, but I couldn’t afford halftones because you had to send those out to a lab for something like $20 a photo and I wasn’t going to spend that much money. So I did this sort of intermediate duotone process, which creates a kind of a quasi-halftone using process film, because I could do that for free from my school’s graphics shop.

Albini [continuing]: When subsequent Big Black records came out and we had the option of doing them in four-color [printing], that meant that I needed to come up with four negatives — one for each color. But I still wasn’t about to pay a professional to do that, so I figured out a way to do a line drawing in black-and-white and then hand-cut the Rubylith, which is a masking material, to create the relief areas for all the other colors. That’s why those record covers — Racer-X, Atomizer, The Hammer Party — are all solid, flat tones. It was entirely practical. Like, if I could have done an elaborate photo session and had a typographer make us a custom font and that sort of stuff, then I would have. But I couldn’t.

UW: Are there any band logos that you particularly like or dislike?

Albini: Very good question that I should have been prepared for. I kind of hate the Rolling Stones lips, but that’s because I hate the Rolling Stones. I should hate the Grateful Dead lightning skull logo, but I don’t in fact hate that logo. I think it’s infinitely better than the band. The Dutch band the Ex, in their early records, had “Ex” in a circle — I always thought that was a really great-looking graphic. They’ve used that a lot, and I’m sure that was another thing where they didn’t want to have to draw something new so they just kept reusing the existing one.

Albini [continuing]: Let me just say, I do think it’s interesting that the Black Flag logo — just the bars — is very much like the Rolling Stones lips or the Grateful Dead skull in that it doesn’t include the band’s name but you still know it’s them. I think it’s kind of amazing. And I’m not the biggest Black Flag fan, but just the simple four bars of the logo is kind of incredible.

UW: How do you feel about a record label using a standardized boilerplate template for the label itself, versus a custom-designed label for each release?

Albini: There’s something charming about it when you have a deep catalog and you can flip through records going back 20, 30 years and you see this consistency. There’s something unifying about it that I admire aesthetically. I don’t think it really matters — like, I’m not pro- or anti- — but when you notice that it’s been the same for 20 years or whatever, that’s kind of charming.

The record label that my band is on, Touch and Go, has a logo that was made using a standard Letraset rub-off typeface that Corey [Rusk, the label founder] did years ago in high school on his mom’s kitchen table. It’s kind of tacky and kind of dumb, but I love that he’s stuck with it all this time.

UW: Similarly, some labels use the same standardized font for the typography on the spine of the LP jacket or the CD case. Any thoughts on that?

Albini: Same thing — I recognize when it’s that way, but it’s not important to me.

UW: Do you sweat those kinds of details when you put out a record by your band?

Albini: Not necessarily those details, but Shellac of North America, we are very careful about the design of our albums. We want things to be just the way we want them, and that can sometimes mean that the execution of them can be stupidly complicated and expensive. Our first album [1994’s At Action Park], we wanted it printed on letterpress so that there would be the debossing of the characters in the paper, and so the graphics would have this very particular look that letterpressed graphics have. And so every time we repress those jackets [for a new pressing of the record, after the previous pressing sells out], we have to find another one of the dwindling number of letterpress printers on Earth. And it just gets incrementally, preposterously more expensive every time we do it, because we have to. And because we credit the printer on the jacket, we have to change the fucking lead type plates to credit the new printer every time.

Albini [continuing]: Our last album, Dude Incredible, the cover is chipboard, so it has that sort of mottled, brownish-grey chipboard look. And the idea was that in the middle of the cover we’d have this color photograph of a monkey throwing another monkey off a cliff. It was a very simple idea: a drab chipboard background with a bright, clear photo printed in the middle of it. And it was an enormous hassle getting that done, because the photo didn’t look right on the chipboard. The problem is that in order to get a vivid color photograph, you need a stark white background. And it proved extremely difficult to print a stark white background onto which you could then print a color photograph. At one point we almost had to commit to just printing up a bunch of color photographs separately and gluing them to chipboard sleeves, because printing it was proving so fucking daunting. We ended up having to do multiple hits of offset opaque white in the rectangular area, flash-curing them, doing the four-color process images of the monkey photo, and then sealing that with a spot varnish so that the ink wouldn’t delaminate from the white base.

Figuring out that printing process took well over a year, so the album was delayed by well over a year. And I just want to stress that all we wanted here was a photograph on paper —we were not asking for, you know, gold foil or 3D-printed sculptural imagery. We had a picture and we just wanted to have this picture printed on paper.

UW: You’re describing this as a big pain in the ass, but I also get the sense that there must have been some pleasure in the problem-solving aspect of this, and the dedication to your vision.

Albini: No, it was pure nuisance. But the fact that we were able to do it —that we have a quite presentable record sleeve with a good-looking picture of a monkey throwing another monkey off a cliff — I’m very happy with the finished result. But the birth pains of it gave me no satisfaction along the way.

UW: Did you consider, you know, maybe changing the parameters a bit, since it was proving to be so logistically challenging?

Albini: All the time! Every time something failed, we would be like, “Fuck it, let’s just glue pictures to the sleeves.” But then someone would have another idea — “Well, here’s one other thing we could try.” So we kept doing it, and at some point it was tantalizingly close. “Oh, we’re very, very close to being able to print a picture of an image on paper. And if we can accomplish this, we will feel like fucking Gutenberg.” Anyway, it has the effect that we wanted, which is that you’re holding this kind of drab cardboard sleeve and this vivid photograph sort of pops out of it.

We’re dealing with a different kind of production issue for our next record. So there’s a new kind of record-pressing process that is ecologically better and has some additional practical benefits, like a lower reject rate, less surface noise, cleaner pressings, things like that. It uses a completely different technology from conventional vinyl record pressing. This new technology uses an injection-molding process of a liquid PET plastic rather than a sandwich press of polyvinyl chloride. So we’re in the middle of the design considerations for a record being manufactured that way, and one issue is the label.

Now, when a record is pressed the conventional way on vinyl, there are two paper labels that go on either side of a big gummy puck of soft, hot PVC that goes into a press. The press smashes down the puck, it exudes out through the stampers, fills the grooves of the record, the excess gets trimmed off, and then you have a vinyl record with labels on either side of it.

But with the new injection-molding process, it’s not possible to add the labels as part of the pressing process. So for every record that’s made, you need to manually apply a label to the A side and the B side, which is tedious and expensive. So in our wisdom, we’ve tried to come up with a way for the label information to be pressed into the record without needing a separate label. We’re using a relief of a graphic element as part of the stamper, so that when the record is pressed, the lettering in the area where the label would normally be is part of the mold for the injection. That way the lettering and graphics are pressed so they appear in relief — not on a printed paper thing on top of it.

UW: Is it a raised, positive relief, or a sunken, negative relief?

Albini: It can be done either way. We’re still fucking around with it. This is for the next Shellac record, which we finished a fucking year ago and still haven’t started pressing.

UW: That’s fascinating. I’m looking forward to seeing that!

Albini: Me even more than you, believe me.

UW: I want to shift gears and talk about another one of your interests, because you’re also a professional poker player and you compete in high-stakes tournaments. What sort of uniforms, if any, are there in the poker world? Or if not actual uniforms, what sort of stylistic conventions or signature looks are there that people tend to have?

Albini: There is a younger generation of poker players — younger than me — who are particularly enthralled with computer solving of poker situations. The computerized solvers can find the optimal plays for certain situations. And these players, especially the ones from Europe, often wear scarves, turtlenecks, they have carefully groomed facial hair — that sort of thing. There’s an air of sophistication about their presentation, which I find super-charming.

There is also kind of a fitness obsession with a lot of the high-stakes players. So you see a lot of people who look sort of like gym rats — they’re really built and extremely lean. Very low body fat.

There are also other accoutrements that you see at, for example, the World Series of Poker that you don’t see anywhere else. The way the World Series of Poker operates is that you have a lot of players racing to the buy-in window after they bust out of one tournament and register for another one. These tournament professionals will often have to carry many tens of thousands of dollars in cash with them — for these buy-ins, or to buy into cash games, or to settle swaps and pieces that they bought of other players. The standard method for carrying all this cash is to have a backpack. So you see these tournament players that look like they’re on an expedition — they’ll have a water bottle, so that they don’t have to leave the table to hydrate themselves. They’ll have their athletic shoes on, they’ll be wearing athletic shorts or sometimes sweats, because they have to scurry back and forth. Also, forgetting your backpack somewhere can be a very expensive proposition, so they’re often quite garish. You’ll often see a guy wearing a scarf with a fluorescent orange book bag and a water bottle.

UW: What about you? How do you typically dress for a tournament?

Albini: I just wear normal clothes. If a friend of mine invites me to be in their celebration shot for their bracelet photo, I like to be wearing the T-shirt of a band that I like. And my favorite one ever was that I was wearing a Killdozer shirt in the bracelet photo for my friend Brandon Shack Harris when he won his second bracelet [in 2016]. So there’s a picture of him and me and all of his friends celebrating, and I’m wearing this threadbare, like 1983 Killdozer T-shirt that’s more holes than shirt, but I’m ecstatic that I was able to keep it alive long enough to wear it in that photo.

UW: So you bring band T-shirts with you to the tournament, just for those photos?

Albini: I basically only wear band T-shirts anyway.

UW: Oh — so when you said you just wear “normal clothes,” band T-shirts are your normal clothes.

Albini: Yeah. About 80% of my wardrobe is band T-shirts. I’ve won two tournaments at the World Series of Poker. When I won the first one [in 2018], I was wearing a shirt from a Belgian band called Cocaine Piss, and their shirt is absolutely magnificent. It’s a cat on ice skates that has been flattened, presumably from being run over. So there’s this dead cat wearing ice skates that’s been run over, and it has “Cocaine Piss.” And then underneath the cat it has “Liege,” which is the town they’re from, with their postal code.

UW: In case anyone thought it might be a different Cocaine Piss.

Albini: When I won my second bracelet [in 2022], I was wearing a T-shirt for a now-defunct band from Athens, Georgia, called the Jackonuts, who were a favorite band of mine in their day.

UW: Obviously, these are pretty obscure reference points. Do other players ever say anything to you about these T-shirts?

Albini: I mean, there are a lot of eccentrics in the poker world. You’ll see a goofball in a top hat or whatever. There are a lot of people who are, like, performatively eccentric. So a guy in a Cocaine Piss T-shirt isn’t that remarkable.

———

And there you have it. Mega-thanks to Steve for sharing his time and stories — it was really fun to reconnect with him after so many years, and I love how we covered so many uni-related issues despite his not being a big sports guy.

• • • • •

One Last “Ask Me Anything” reminder

The next quarterly installment of “Ask Me Anything,” the series where you can ask me anything about uniforms, sports, Uni Watch, me, or anything else, and I do my best to answer, will be published this month — probably next week! If you’d like to submit a question, feel free to email it here. (Please note that this is not the usual Uni Watch email address.) One question per person, please.

I look forward to seeing your queries. Thanks!

(If you enjoyed this post, please consider “liking” it by clicking the ❤️ button below, which will help more people discover it on Substack. Thank you!)

Paul Lukas has been writing about uniforms for over 20 years. If you like his Premium articles, you’ll probably like his daily Uni Watch Blog, plus you can follow him on Twitter and Facebook and check out his Uni Watch merchandise. Have a question for Paul? Contact him here.

Damn, this was fantastic. Loved the intersection of uniform and logo minutiae in music and pop culture, and the band logo discussion was just great. Steve was such an engaging subject, bravo all around.

OMF-ingG! What an incredible interview for a music nerd like me! Thanks Paul.