Boundary Issues, Day 4: The Myth of Border Width

It’s the fourth installment in our weeklong look at territorial borders.

This post is part of a weeklong series of articles about territorial borders, called Boundary Issues. You can see other articles in this series, along with the article from last week that inspired this week’s content, here. All articles this week are non-paywalled. Enjoy!

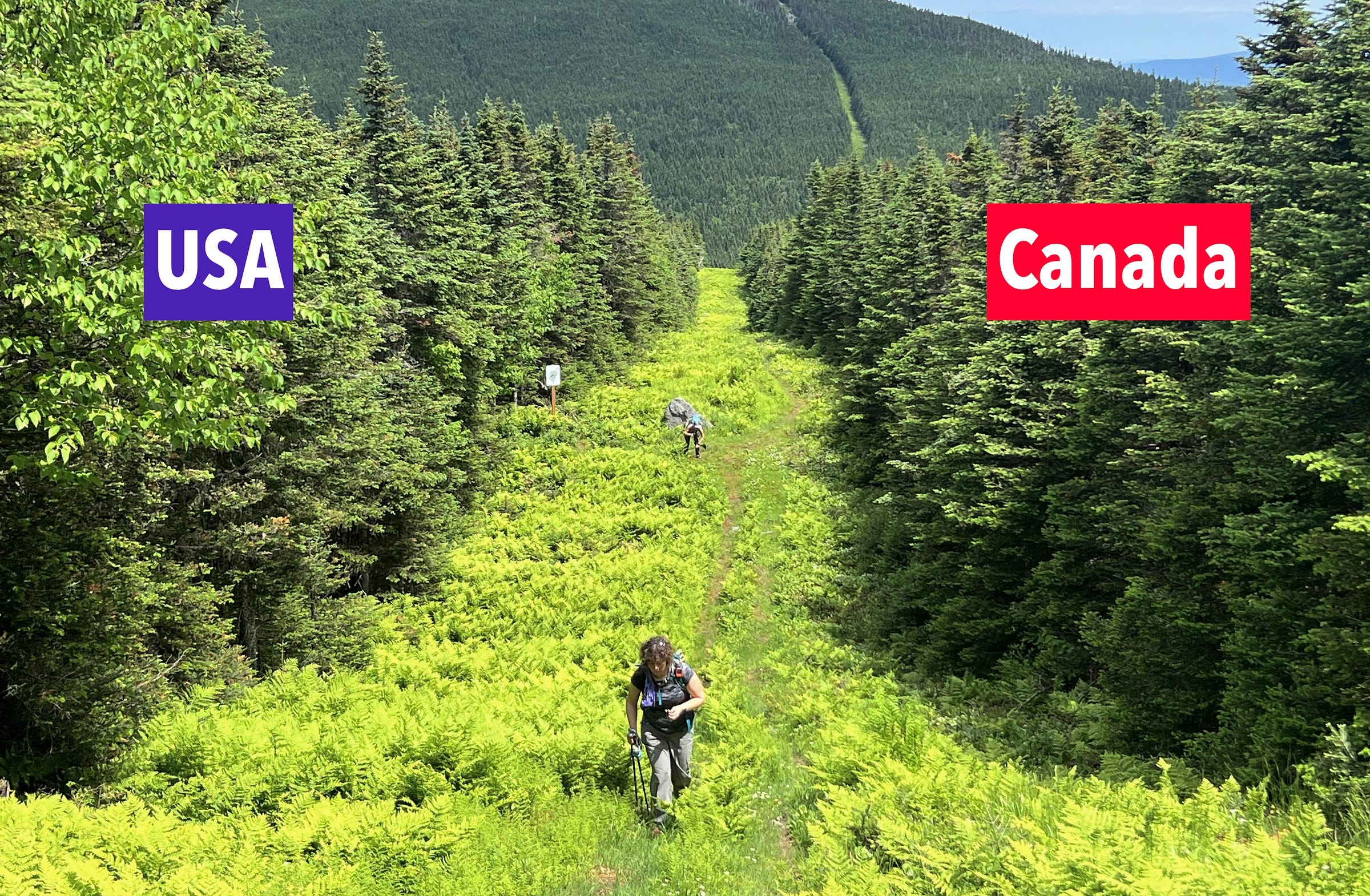

I’ve included several recent mentions of the Slash, which is the deforested strip of wilderness that marks a lengthy stretch of the U.S./Canada border (as seen above). The Slash, which is actually visible in satellite photos, is a particularly vivid example of how we tend to demarcate borders with some sort of linear visual device. Usually, of course, the device is much simpler and smaller, like a fence or a wall. The simplest device of all is a line painted on the ground. Here, for example, is one of several painted lines that mark the border between the Netherlands from Belgium:

And here’s a painted line — or, more specifically, a dashed white line painted within a thicker blue painted line — marking the border between Ohio and Kentucky on the Newport Southbank Bridge:

Painted lines like these are common because they’re intuitive. When two roommates can’t stand each other, what do they do? They paint a line down the center of the room and say, “You stay on your side and I’ll stay on mine!”

So what do the U.S. and Canada do when their border is in a developed area, instead of in the wilderness? They often use a painted line, like this one in Derby Line, Vermont (note that the period after the “A” is missing!):

Derby Line is also the location of the Haskell Free Library and Opera House, which famously straddles the international border — a border that is marked within the library by, of course, a painted line:

All of which leads me to this: The Slash is 20 feet wide; the line painted on the street in Derby Line appears to be about a foot wide; the line painted in the library appears to be maybe two inches wide. But how can all of those be true? Did the border shrink? Does it have an uneven width?

The answer, of course, is that a border has no width at all. But the visualization devices we use — painted lines, clear-cut strips of deforestation, and so on — create the illusion of a border having a certain thickness. I call this the myth of border width.

To see what I mean by that, imagine there are two adjacent territories called Greenville and Yellowville. An overhead view of these two territories might look like this:

That seems simple enough: There are two territories, and the border is where they abut.

But let’s say the folks in Greenville and Yellowville decide to demarcate their border by painting an orange line on the ground. So now the overhead view will look like this:

Once you add a line, there are essentially three territories: Greenville, Yellowville, and the orange line itself. It doesn’t really matter if the orange line is 20 feet wide, one foot wide, a few inches wide, or even just one micron wide. The point is, once you physically draw a line (or build a fence, or erect a wall, or clear-cut a swath of trees, or whatever), you’re delineating a strip of territory with length, width, and thus area. And that area can add up: If we multiply the Slash’s 20-foot width by its 1,349-mile length, that amounts to about five square miles of land!

The reality, of course, is that the border is the lateral midpoint of the Slash, or the painted line, or whatever. So when we create this type of visual device, we’re really marking a buffer zone around a border, rather than marking the border itself. Some buffer zones are officially designated as such, like the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea. But more often they’re unintentional, created as byproducts of border-visualization devices.

Border monuments, which we talked about earlier this week, are similarly imperfect. They provide the illusion of precision — their locations are based on geological surveys, after all — but they’re inherently imprecise because they occupy space. (Indeed, some of them are much wider at the base than a typical painted line.) So you end up with Territory A being on one side of the monument and Territory B on the other side, but what about the land occupied by the marker itself?

All of this is what tends to happen when you take an abstraction (the border) and try to make it visible or tangible. It would be interesting to know how much land around the world is occupied by all these painted lines, monuments, fences, walls, and so on.

Borders aren’t the only things that behave this way. Lines of longitude and latitude, for example, are also abstractions. They have an implied precision, but that precision is lost as soon as we make them visible by drawing them on a map (or on the ground, or wherever). Why? Because any line we render will have a certain thickness, and that thickness will, by definition, extend around the locus of points it represents, just like the Slash or a painted border line. (Unsurprisingly, many territorial borders are defined by lines of latitude and longitude, including a long section of the U.S./Canada border, which by treaty is set at the 49th parallel.)

Sometimes there’s no intentional border-visualization device, but something ends up demarcating the border anyway. In 2019, for example, I was driving in Northern Ireland and crossed the border into Ireland. Surprisingly, there was no official acknowledgement of the border crossing — not even a “Welcome to Ireland” sign. But it was still easy to see where the border was, because the pavement pattern on the road changed.

Although there’s no painted line, you can see that there’s a line of blacktop sealant running across the roadway, which serves as a handy visualization device. But, of course, the sealant line occupies space and is thus imprecise. The myth of width! If there were no sealant and two pavement patterns simply abutted, that would be a more accurate depiction of the border (but a lower-quality method of roadway engineering).

Does the myth of width really “matter” in any practical sense? Probably not. But it’s one of many border-related topics that I find interesting to ponder.

Tomorrow we’ll wrap up our weeklong Boundary Issues series with one final blitz of border-related curiosities. See you back here then!

Paul Lukas has been obsessing over the inconspicuous for most of his life, and has been writing about those obsessions for more than 30 years. You can contact him here.

A phenomenon I wanted to mention before this series ends -- how different state borders are viewed depending on where you live. My friends in the east think nothing of bouncing from state to state in the course of commutes or quick trips or the like. But I live in the Bay Area, where it's more than three hours to Nevada and about five hours to Oregon.

Near the end of my block, my street exits my city and enters unincorporated county land and the clearest demarcation is definitely the change in road surface. Over the years, which side was smoother has varied based on which entity has more recently resurfaced roads in the area.