Some Thoughts About Booing at the Ballpark

I’ve spent most of my life booing when I thought it was warranted. But now I’m rethinking that.

A little over a month ago I ran a think piece on the Uni Watch blog about fan behavior at the ballpark. One of the sections in that piece was about booing, and I wrote this: “If the team really stinks over an extended period, or if a player is really underperforming, then sure, booing makes sense.”

In the comments for that post, several readers made a point of saying that they never boo, which surprised me. I was particularly struck by a comment from longtime reader Dave Murray, who wrote: “I stopped booing after getting to do some stories about players and getting to know them and their lives. I see them more as people now.”

That comment really jumped out at me. It also got me thinking about two things. First, there was a Uni Watch post from last year in which I wrote about tennis star Naomi Osaka withdrawing from the French Open after saying that press conferences were difficult for her and that she needed to focus on her mental health. Her situation got me thinking about how things like emotional health and work/life balance apply to athletes. As I wrote at the time:

I’ve always been a bit uneasy about being in a team’s clubhouse [as a reporter] — not because I’m starstruck by the players or anything like that, but just because I think it’s really strange to be interrogating people at their workplace. ... We’re so used to the sports world working this way that it’s easy to forget how weird it is.

[…]

I’ve often wondered how many potentially great players there are who never make it to the big time because they possess the physical skills but can’t handle the travel, or the press, or playing in a different country with a different language, or playing in front of big crowds, or the homesickness, or the toll on their families, or the toll on their mental and emotional health, or whatever. Most of those athletes get weeded out in their teens or early 20s, so we never hear about them.

Although the Osaka situation wasn’t about booing, it was definitely about seeing athletes “more as people,” as Murray put it in his Uni Watch comment.

The other thing I thought about when I read Murray’s comment was a situation that unfolded last August (about two months after I wrote the post I just quoted from), when several Mets players began giving a thumbs-down sign after getting a big hit or winning a game. When questioned about it, they said the thumbs-down was their way of booing the fans back after the fans had booed them. One player, Javier Báez, said at the time, “It feels bad when I strike out and I get booed. It doesn’t really get to me, but I want to let them know that when we have success, we’re going to do the same thing, to let [fans] know how it feels.”

Unsurprisingly, the reaction to this from fans, media outlets, and team management was overwhelmingly negative. (Mets GM Sandy Alderson posted an apology, noting that “Booing is every fan’s right.”) As a Mets fan myself, I was pissed off at the players too. But at the same time, a little part of me empathized with what Báez was trying to convey. Although the thumbs-down gesture and his explanation for it both seemed like clumsy messaging at best, I sensed that he and the other Mets were trying to say something like this: “We’re trying our best. Aren’t the players and the home fans supposed to be on the same side? Do you really think booing will make us play better? Why would you want to humiliate us like that? We're human, too; we have feelings, too.”

And that’s really what I think all of this is about: Despite all the hype, players aren't superheroes, they’re not machines, they’re not ”warriors” or “legends” — they’re just people. Sometimes we forget that. It reminds me of a scene from an early episode of The Simpsons (“Homer at the Bat” — Season 3, Episode 17), in which Bart and Lisa heckle Darryl Strawberry:

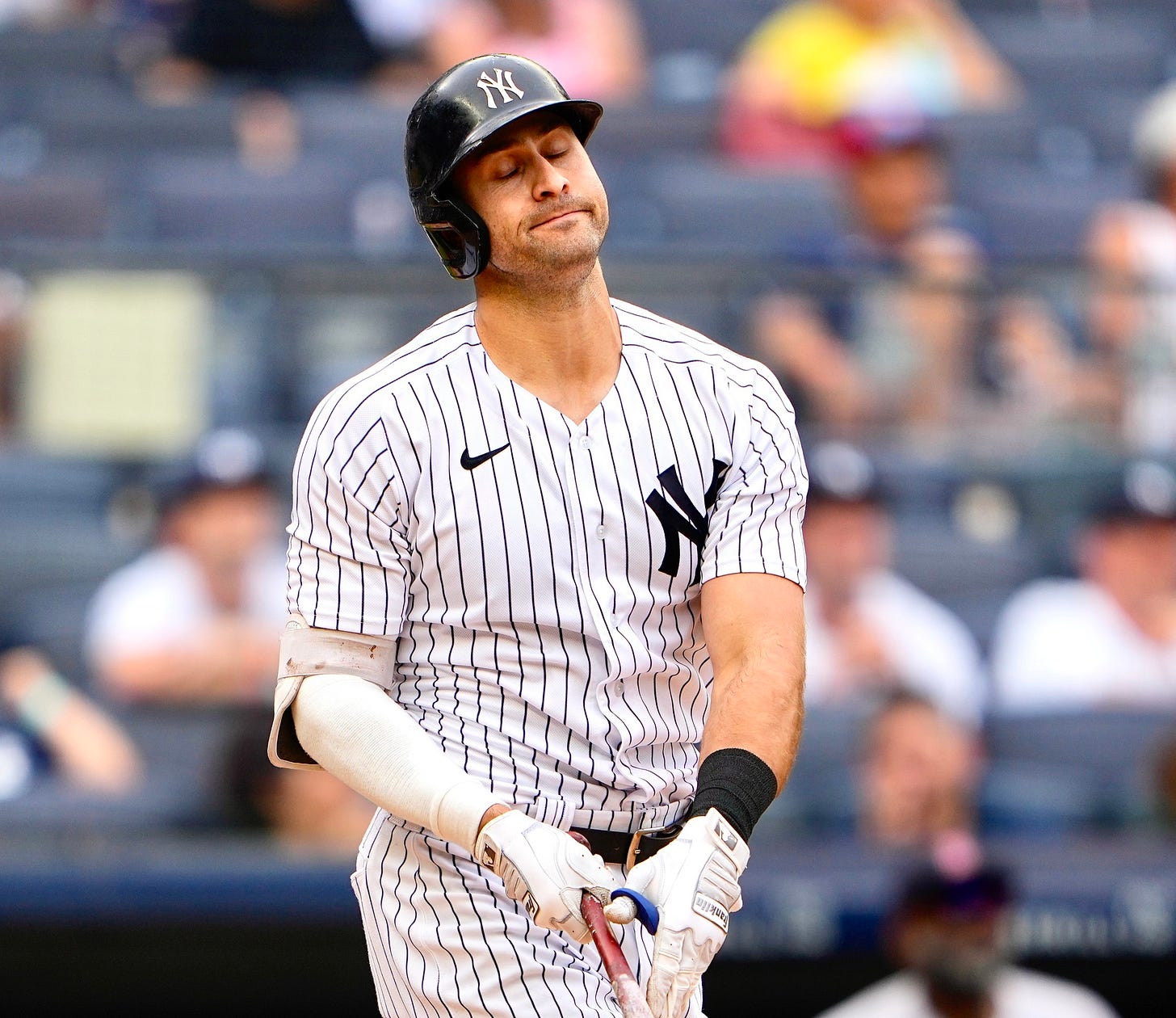

While I was thinking about all of this (and working on a rough draft of this essay), something else happened: The Yankees traded outfielder Joey Gallo, who was having a terrible season and being booed relentlessly by the hometown fans. On his way out the door, Gallo admitted that the boos had affected him. That led Yanks TV broadcaster Michael Kay to offer this analysis:

[Gallo] was a failure here in New York, for whatever reason. Whether the pressure of having to win became a big deal, whether he just got his swing out of whack because he mentally was not right while he was here, he deserved to be booed. I don’t think the fans were extra-special hard on him. I look at what the fans did to Giancarlo Stanton when he first got here — that was unfair. I mean, the first game he ever played here, they booed him. But this guy [Gallo] earned the boos.

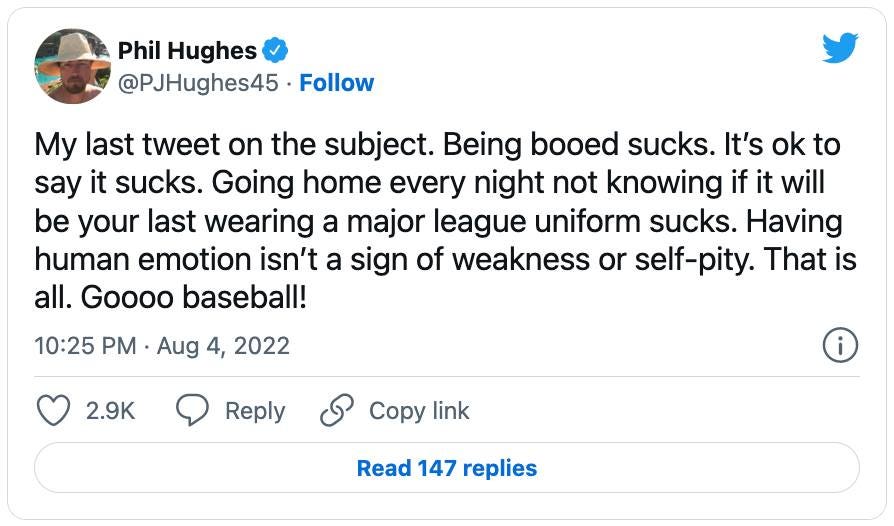

Kay’s on-air commentary led to a social media spat between him and former MLB pitcher Phil Hughes, who took issue with Kay’s assessment that Gallo “deserved to be booed” and had “earned the boos.” Hughes, who played for the Yankees himself from 2007 through 2013, concluded his dialogue with Kay by tweeting this:

Hughes was basically saying the same thing that Osaka, Báez, and Gallo said: “We’re human. We have feelings and emotions just like everyone else.” But Hughes also went further by taking direct aim at the toxic notion that being stoic and unfeeling is a sign of strength and that showing emotion is a sign of weakness, a malignant fallacy that has permeated sports, and our larger society, for much too long. (As an aside, Hughes also gets bonus points for referencing his uniform.)

I respect these athletes for taking these stands. And that’s why I’ve decided I’m not going to boo individual players anymore, especially the ones on the teams I’m rooting for, at least not for things like striking out or blowing a save. (There are a few potential exceptions in other situations, which I’ll get to in a minute.) I might generally boo the opposing team during pregame announcements or something like that, just as a bit of light theater, but I’m not going to boo a player for playing poorly, or boo my team for losing. Booing may be my right, as Sandy Alderson said, but that doesn't mean it’s the right thing to do.

I think my “no booing” policy will be better not just for the players but also for me, because on some level booing feels like a form of bullying, a form of punching down, and those are things that always leave me feeling worse in the long run, no matter how satisfying they may feel in the moment.

I can imagine some of the reactions to what I’m saying here. For example:

Why shouldn’t I boo a bad player? I pay his salary!

Sure, but we also pay the salary of the staff at the restaurants where we eat, the barber who cuts our hair, countless elected and appointed civil servants, and a lot of other people. Do we boo any of them?

These athletes get paid millions of dollars to play a kid’s game. They should be able to handle some booing!

Honestly, I’ve never understood the “kid’s game” argument. When you refer to baseball (or any sport) as a “kid’s game,” you’re trivializing it, deriding it, saying it doesn’t really matter. Of course, baseball and other sports don't matter compared to things like cancer or climate change, but sports are still a big part of our culture — that’s why you follow the games (and read Uni Watch) to begin with! Why would you trivialize something you care about? If it’s just a “kid’s game,” why even bother with any of this?

If we remove the “kid’s game” argument from the equation, we’re basically left with “These are spoiled, rich athletes” (which really is just another way of saying, “I pay their salary”). Yes, they make a lot of money — so what? Are you really booing as a form of class warfare? Should the homeless guy on the sidewalk boo you as you walk by? After all, you’re a lot wealthier than he is!

I think the fact that the players make so much money is a big part of why it’s so easy to stop thinking of them as human beings. But again, they’re just people, same as the rest of us.

How can you refer to fans booing as “bullying” or “punching down”? The players are bigshot celebrities and I’m just a nobody in the crowd!

You’re correct regarding the fans’ and players’ relative social status, but that’s not what I was referring to. What I meant was that fans can boo with impunity and there’s really nothing the players can do in response. (Or if they do try to respond, as those Mets players did, they get scolded for it.) So it’s essentially a one-way power dynamic, which to my mind is the definition of punching down.

This is all ridiculous. Sure, I don’t boo the cashier or the restaurant staff if they fuck up, but I also don’t applaud them if they do their jobs well. Athletes aren’t like other workers — they’re entertainers, so booing comes with the territory, just like applause.

Actually, most other live-performance entertainers don’t get booed. If a guitarist screws up his solo during a rock show, or an actor flubs her lines during a play, or a circus clown drops something he’s juggling, you probably don’t boo any of those people, right?

Anyway, the whole notion of what “comes with the territory” is always in flux, because our society is constantly redefining what is or isn’t culturally acceptable. At one point, belittling something by saying, “That’s so gay” was okay; now, thankfully, it’s not. The same may eventually be true — or maybe is now becoming true — for booing.

This is all part of the wussification of America. That’s the problem with society nowadays — everyone’s too sensitive, too soft. Now you’re telling me we can't even boo a ballplayer because it might hurt his wittle feewings? Gimme a break!

I dunno. When I look around at our society, I see people screaming at sales clerks and flight attendants, people berating each other on social media, people being rude to each other at work, and other forms of rising incivility. (And that’s just the everyday stuff — we could also include more extreme examples like the Jan. 6 insurrection and mass shootings.)

So with all due respect, the general state of things doesn't seem “soft” to me at all. If anything, I think we could use a bit more softness.

I live in Philadelphia. Booing is in my DNA!

If you say so. But is that really what you want to be known for?

What about booing the ump?

Razzing the umpire is certainly a time-honored form of theater. (I especially like the old routine of the ballpark organist playing “Three Blind Mice” when the umps come onto the field before the game.) But with replay review, we now have very few truly bad calls — if the ump misses a call, it’s usually overturned. So do “Come on, blue!” situations even come up anymore? Seems mostly like a moot point.

When channeling what the Mets players were attempting to communicate, you began with “We’re trying our best.” But what about when a player isn’t trying his best? What if he’s dogging it, not hustling, and so on?

I agree that that’s a trickier situation. I was once at a game in which Rickey Henderson, who was then with the Mets, hit a ball off the wall. He should have ended up on second base with a double, but instead he was at first because he stood to admire what he thought was going to be a home run. (This later led to one of the all-time great Rickey quotes: “I hit it out but it didn’t go out.”) I was livid, and I booed long and hard. Would I respond the same way today? Yeah, maybe. But I’d like to think that the non-hustling player’s teammates and manager would say something to him — that form of self-policing seems like a better way to set things right than booing does.

Also, where do you draw the line? Sticking with the Mets, for example, outfielder Brandon Nimmo hustles as much as any ballplayer I’ve ever seen. Compared to him, everyone else is dogging it. Would I prefer that everyone hustle as much as he does? Yeah — it seems like a fairly straightforward thing. But am I going to boo every other player because they don’t meet Nimmo’s standard, even though I think the standard he sets should be simple enough for everyone else to meet? Of course not.

What about booing someone because they’re a bad person, not because they struck out or didn’t hustle?

I agree that athletes like Deshaun Watson, Trevor Bauer, and Ray Rice present a different set of parameters. If the Mets somehow signed Bauer (which will never happen now, although it almost happened two off-seasons ago!), would I boo him? I guess I would if I attended a game in which he pitched, but I think I’d be more likely to boycott any games when he was scheduled to pitch.

On the other hand, I didn’t boycott Robinson Canó, a past (and future) steroid cheater, when he was a Met. I even cheered for him! So is this really about standing up for principles and values, or is it more about finding the easiest target and piling on? Hmmmm.

It’ll be interesting to see how fans in Cleveland treat Watson when he returns from his suspension this December — especially if he plays well.

Look, I get what you’re saying in this article. But there has to be some kind of accountability, right? If I have a problem with an employee at a traditional business, I have lots of options: I can ask to see the manager, lodge a formal complaint, leave a negative Yelp review, or just take my business elsewhere. But at the ballpark, booing is my only option.

Well, you could still take your business elsewhere — stop buying tickets and stop rooting for the team. But many fans don’t view that as a viable option. And I think this all comes back to uniforms: As I’ve written many times, we continue to root for whoever’s wearing that uniform, creating a fan/team bond that’s completely irrational and thus extremely powerful. If you feel on an emotional level like you’re tethered to the team — like you’re almost stuck with the team — then yeah, I can see how booing might seem like the only recourse when a player performs poorly. It’s almost like a way of saying, “I’m stuck with you, and you’re stuck with me too!”

But is that really a form of accountability? Is booing going to make a player play better? Or is it just a cathartic release?

Personally, I’ve decided I can live without that catharsis. And like I said earlier, I think I’ll be better off for it.

But that’s just me. If you want to boo, of course that’s still your prerogative. I won’t be joining you anymore, though.

(My thanks to reader Dave Murray, whose comment on that July blog post prompted me to think harder about this topic.)

• • • • • • • •

NFL Season Preview Final Countdown

We’re now less than a week away from the start of the NFL regular season on Sept. 8, which means we’re also closing in on the annual Uni Watch NFL Season Preview. This is always one of my most anticipated columns of the year, and it’ll be even more info-packed than usual this time around because of all the new helmet designs that have been released in the past few months.

I’m putting the finishing touches on the NFL Preview as we speak, and I don’t mind saying that it’s a doozy. It will be published here on Bulletin on the morning of next Tuesday, Sept. 6, and the NBA and NHL Season Previews will follow in October. But unlike this article that you’re reading right now, the Season Previews will be paywalled. So if you don’t already have a Premium Subscription, you might want to consider getting one now.

• • • • • • • •

“Ask Me Anything” Reminder

A week or two after the NFL Preview, I’ll have the latest installment of our ongoing “Ask Me Anything” series, where you folks can ask me a question — about uniforms, about Uni Watch, or just about me — and I do my best to answer. (You can see previous installments here, here, here, and here.)

If you’d like to submit a question, feel free to email it here. (Please note that this is not the usual Uni Watch email address.) One question per person, please. I look forward to seeing your queries!

Paul Lukas has been writing about uniforms for over 20 years. If you like his Bulletin articles, you’ll probably like his daily Uni Watch Blog, plus you can follow him on Twitter and Facebook and check out his Uni Watch merchandise. Have a question for Paul? Contact him here.